As part of a Carver College of Medicine delegation, Dr. Kanwal Matharu and I recently traveled to Zambia, where we met with leaders from UIHC, International Vision Volunteers, and Hilary Twiggs from Orbis. One of the most impactful stops on our trip was the House of Hope, a transformative organization focused on children with hydrocephalus and spina bifida.

Founded nearly a decade ago with the help of Dr. Rebecca Reynolds (Neurosurgery), the House of Hope combats the deep-rooted stigma surrounding these conditions. In parts of Africa, such diagnoses are tragically linked to beliefs in witchcraft—leading, in some cases, to infanticide. The House of Hope offers an alternative: education, medical support, and empowerment for families.

They provide safe housing, coordinate hospital visits, and teach parents how to care for their children. One inspiring initiative teaches families how to grow and cook nutrient-rich food, helping sustain their children’s health. Perhaps most powerfully, mothers are encouraged to become advocates—returning to their villages to raise awareness and break the cycle of stigma.

Dr. Reynolds, former Dean, Brooks Jackson, and University Teaching Hospital (UTH) staff are now exploring ways to integrate ophthalmic care into the House’s services. Since hydrocephalus often affects the optic nerve, early eye assessments could be life changing. We're working toward equipping the facility with a dedicated exam room and essential tools for immediate eye evaluations.

During our visit, we also toured eye clinics at UTH and Levy Mwanawasa University Teaching Hospital. We met with leaders who voiced an urgent need for better training in pediatric ophthalmology, nursing curriculum, instrument care, and RetCam use. Dr. Matharu led a hands-on wet lab for second-year students, who were eager and incredibly appreciative.

We saw firsthand the challenges: overcrowded clinics, paper records, and sweltering rooms with no air circulation. One patient—a 24-year-old woman—needed bilateral corneal transplants after a severe infection. But without eye banks or trained corneal surgeons, treatment options remain heartbreakingly limited. Cultural beliefs around organ donation compound the issue, creating a severe tissue shortage.

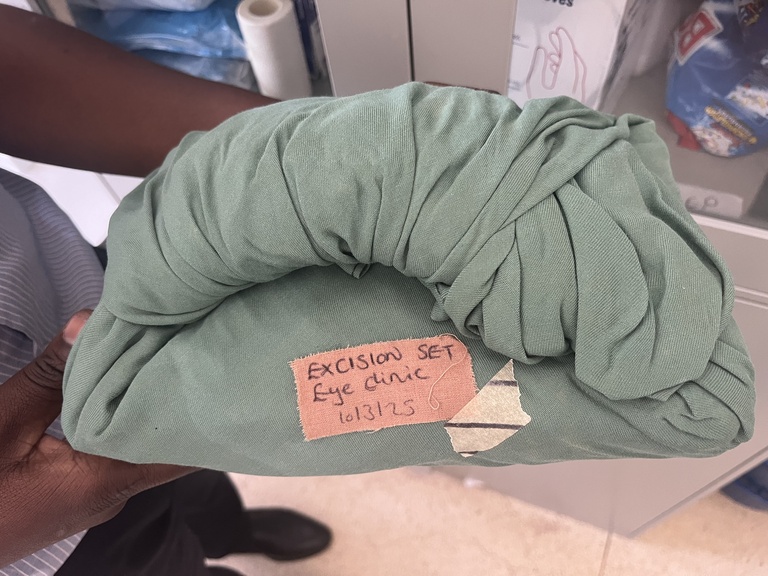

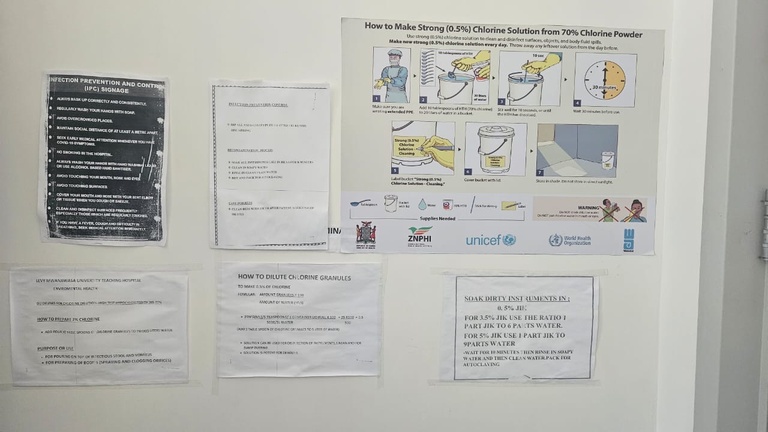

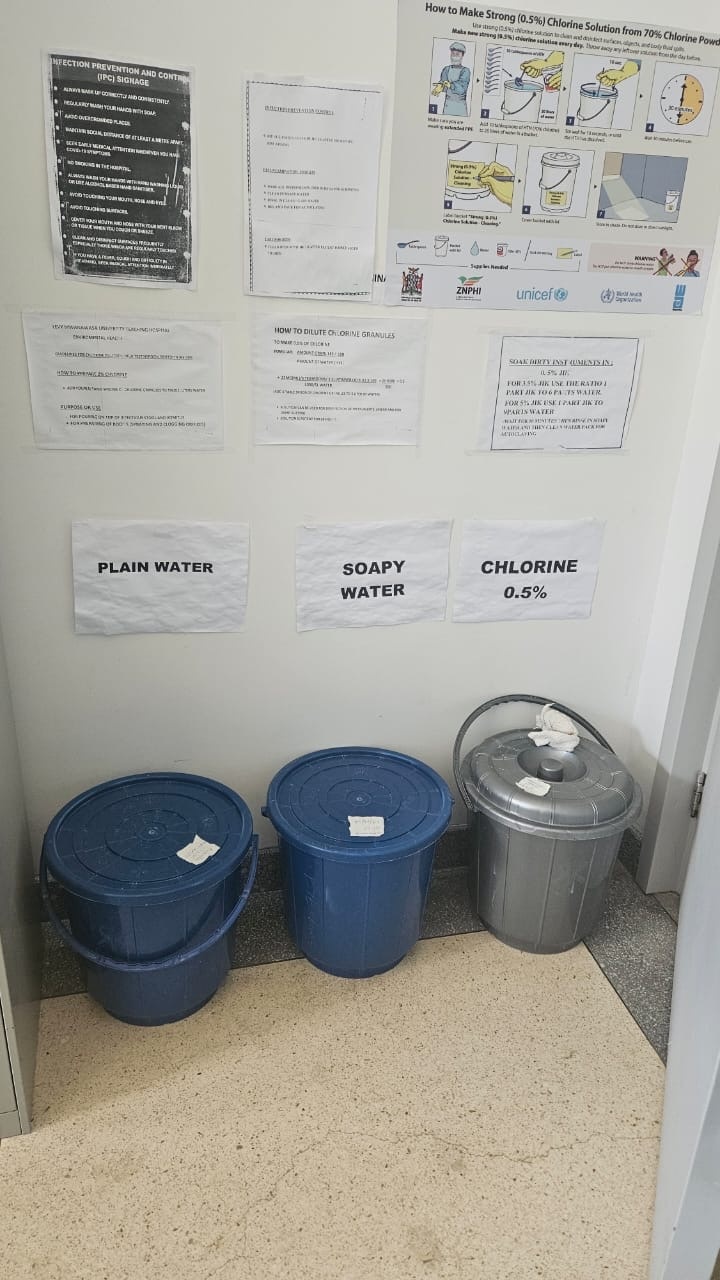

Sterilization practices also differ. Instruments are soaked in chlorine, washed, rinsed, and then run through a small sterilizer—before being placed unwrapped in open trays for reuse. It's a system born of necessity, but one that highlights the need for improved infrastructure and training.

Finally, we visited the Orbis Zambia office, where the team shared their incredible 15-year journey advancing eye care in the region. I’ll be collaborating with them to develop subspecialty curriculum for their Cybersight platform—bringing high-quality education to remote providers around the world.

This trip was a powerful reminder of the impact of partnership, education, and community-led care. There's still much to be done—but hope is growing.