Main navigation

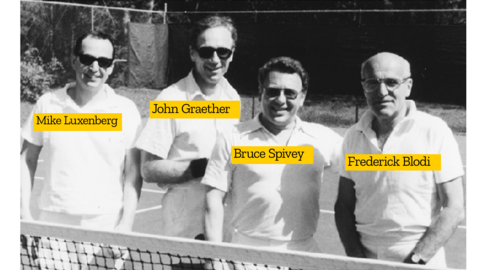

The period from 1965 to 1974 was a transformative era for the University of Iowa's Department of Ophthalmology. Under the visionary leadership of Dr. Frederick C. Blodi, who took the helm in 1967, the department experienced remarkable growth and innovation. This decade laid the foundation for many of the modern advancements in ophthalmology that we benefit from today.

Leadership and Faculty Expansion

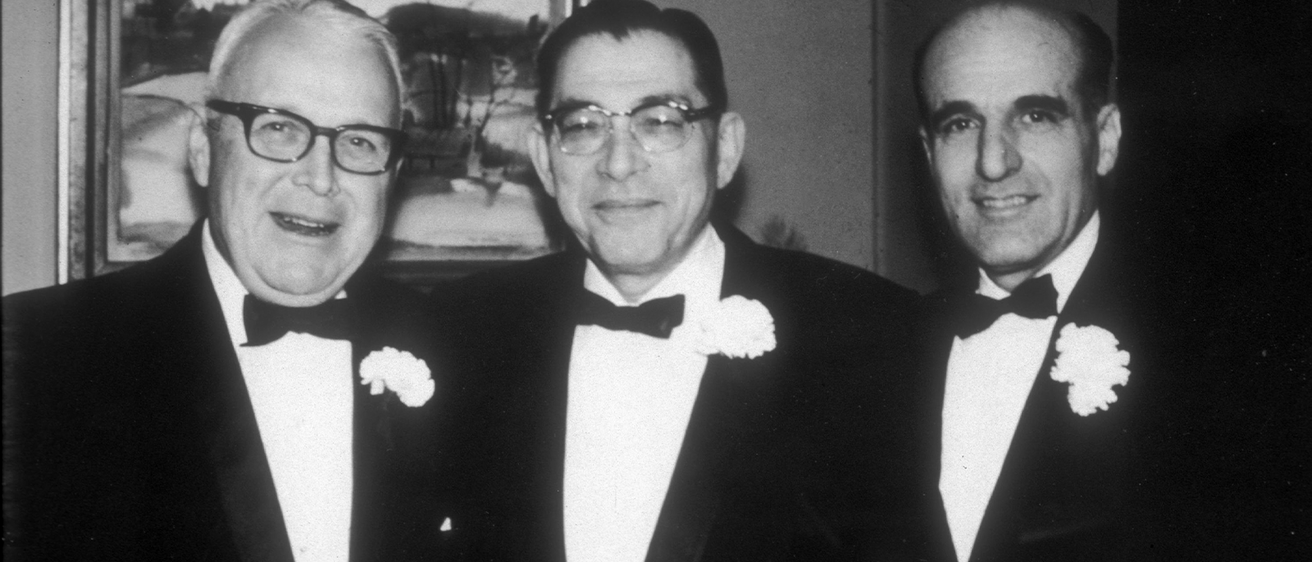

The period from 1965 to 1974 was marked by significant leadership changes and faculty growth at the University of Iowa's Department of Ophthalmology. In 1967, Dr. Frederick C. Blodi succeeded Dr. Alson E. Braley as the head of the department. Dr. Blodi's leadership was pivotal in steering the department towards new heights of excellence in both clinical practice and research.

Faculty Expansion and Collaboration

The department's growth was not limited to individual faculty members. Dr. Blodi fostered a collaborative environment, encouraging interdisciplinary research and partnerships with other medical and scientific disciplines. This approach enhanced the department's research capabilities and facilitated the integration of new diagnostic and surgical techniques into clinical practice.

Research and Educational Initiatives

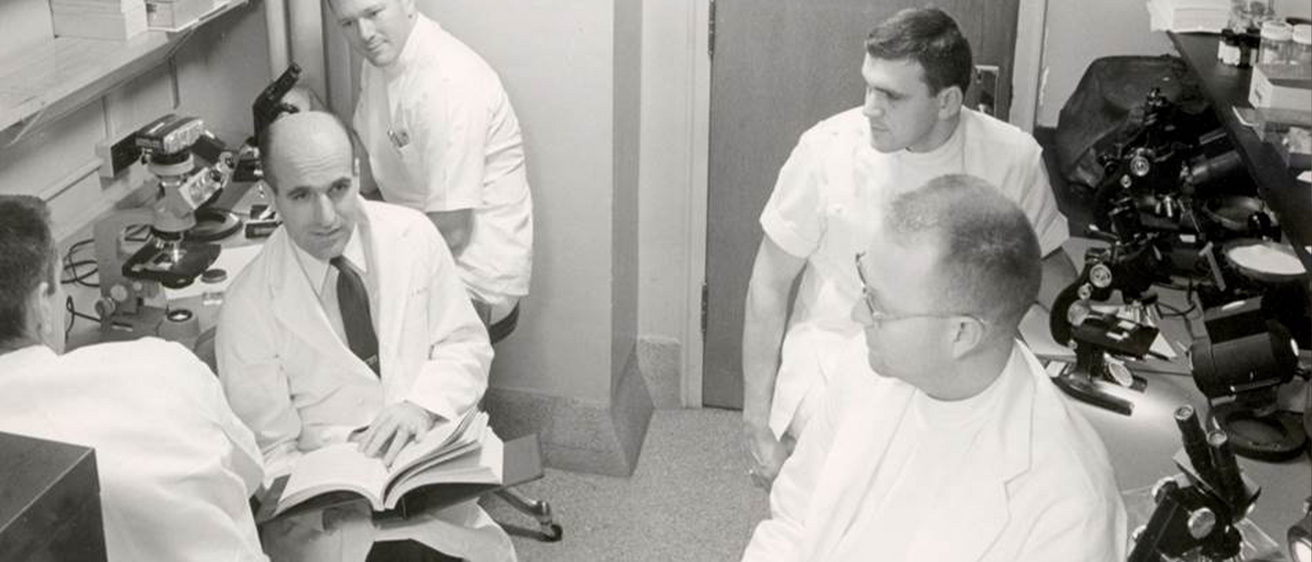

The expanded faculty brought with them a wealth of knowledge and experience, which was instrumental in the development of new research initiatives and educational programs. The department's residency and fellowship programs were expanded to accommodate more trainees, providing them with comprehensive education that integrated clinical practice with cutting-edge research.

Regular seminars, conferences, and grand rounds were organized, allowing faculty, residents, and fellows to present their research findings and discuss clinical cases. These events fostered a culture of inquiry and collaboration, essential for the department's continued growth and innovation.

The department's research efforts during this period were particularly focused on retinal diseases and glaucoma. Innovative diagnostic techniques were developed, enhancing the understanding and treatment of these conditions. The introduction of advanced imaging technologies allowed for better visualization of retinal diseases, leading to improved patient outcomes.

Clinical trials and studies were conducted to explore new treatments for retinal diseases such as age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and diabetic retinopathy. The department's interdisciplinary collaborations further enriched its research capabilities, integrating insights from various medical and scientific fields.

In the realm of glaucoma, significant strides were made in early detection and monitoring. New screening methods and advanced imaging techniques were developed to track disease progression. Research efforts also led to the development of new medications and surgical techniques aimed at reducing intraocular pressure and preventing vision loss.

Educational Program Growth 1965-1974

Under the leadership of Dr. Frederick C. Blodi, the department expanded its residency program to accept five residents per year and increased its fellowship offerings to include subspecialties such as glaucoma, retina, and cornea. This period marked a strong emphasis on integrating clinical practice with pioneering research, particularly in areas like ocular microbiology and cataract formation.

Trainees received comprehensive hands-on training in both clinical and surgical settings, with opportunities to work on innovative techniques and technologies. This was complemented by exposure to cutting-edge research, including advancements in fundus photography and gonioscopy. The department's approach ensured that graduates were well-prepared to become leaders in the field of ophthalmology.

Regular seminars, conferences, and grand rounds provided platforms for knowledge exchange and collaboration. These events often featured prominent guest speakers and facilitated discussions on the latest advancements in ophthalmology. Experienced faculty members, including renowned figures like Dr. Mansour F. Armaly, offered mentorship and guidance, nurturing the next generation of innovative ophthalmologists.

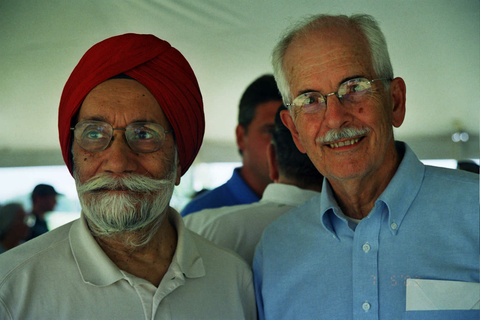

The Visionary of Vascular Ophthalmology: Dr. Sohan S. Hayreh

Early Life and Education

Dr. Sohan S. Hayreh, born in 1927 in Littran, Punjab, India, is a renowned ophthalmologist known for his groundbreaking research on the vascular circulation of the visual system and vascular diseases of the eye and optic nerve. Despite the challenges of growing up in a farming community where education was not prioritized, Dr. Hayreh's mother was determined that he would become a physician. He attended King Edward Medical College in Lahore, later moving to Punjab Medical College in Amritsar due to the partition of India, and earned his M.B.B.S. in 1951 and Master of Surgery in 1959.

Early Career and Research

Dr. Hayreh's early career included a surgical residency and a position as a Medical Officer in the Indian Army Medical Corps, which he used to supported his family financially. He then joined the anatomy department at

Government Medical College in Patiala, India, where he conducted significant research on the anatomy of the eye's vasculature. His work caught international attention, leading to a prestigious Beit Memorial Research Fellowship in 1961, which allowed him to move to London and work with Sir Stewart Duke-Elder at the University of London. His research during this period formed the basis of his Ph.D. thesis.

Academic and Professional Achievements

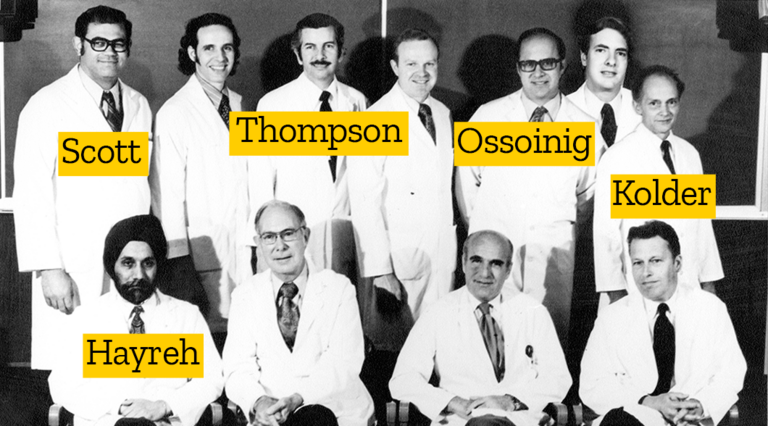

Joining the University of Iowa Department of Ophthalmology in 1973, Dr. Hayreh focused his research on ocular vascular disorders and optic nerve disorders, including glaucoma. He established the Ocular Vascular Experimental Laboratory and the Ocular Vascular Clinic, which became pivotal in advancing research and clinical practices in these areas.

One of Dr. Hayreh's notable achievements was the establishment of the Ocular Vascular Experimental Laboratory and the Ocular Vascular Clinic. These facilities, supported by research grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), allowed Dr. Hayreh to conduct extensive clinical and experimental research. His work in these labs led to groundbreaking discoveries in the understanding of ocular vascular diseases and optic nerve disorders.

Groundbreaking Research and Discoveries

Dr. Hayreh made several seminal contributions to ophthalmology during his time at the University of Iowa. He solved the long-standing enigma of the pathogenesis of optic disc edema in raised intracranial pressure, a mystery that had persisted since 1853. He also corrected misconceptions about the posterior ciliary artery and its role in the blood supply of the optic nerve head. His research demonstrated that nocturnal arterial hypotension plays a crucial role in optic nerve and ocular vascular ischemic disorders, significantly advancing the understanding of these conditions. His work on ocular circulation in health and disease, particularly optic nerve disorders, was considered groundbreaking and influential.

Continued Impact and Legacy

Dr. Hayreh's impact on the field of ophthalmology extends beyond his tenure at the University of Iowa. He published over 400 original peer-reviewed articles, six classical monographs, and more than 50 chapters in ophthalmic books. His research has influenced clinical practices and furthered research worldwide. Even after assuming professor emeritus status in 1999, Dr. Hayreh remained active in research and publishing, continuing to contribute to the understanding and treatment of vascular eye diseases. Dr. Hayreh's dedication to his field and his numerous contributions made him a respected figure in the medical community. His work continues to benefit patients and practitioners, solidifying his legacy as a pioneer in ophthalmology.

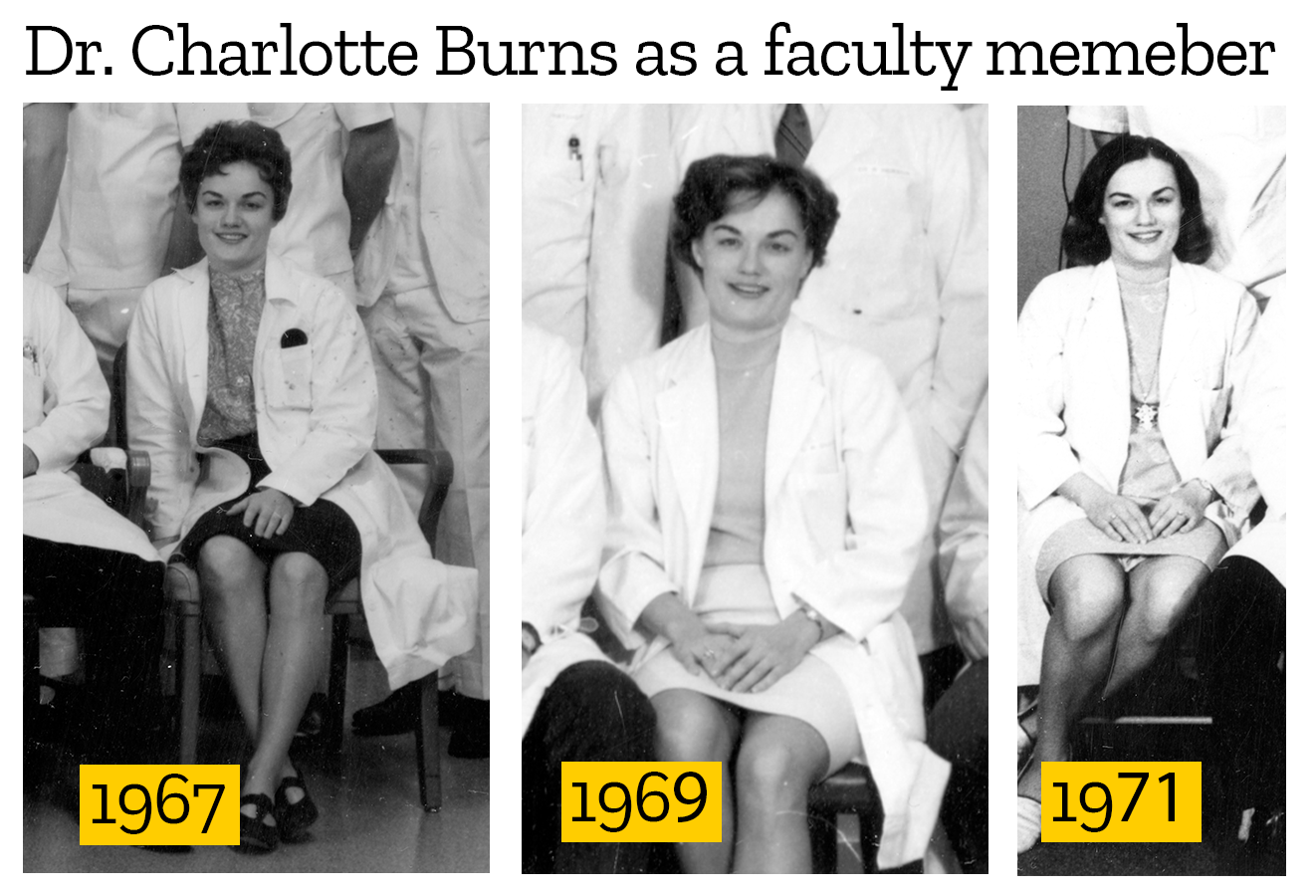

Dr. Charlotte Burns—Iowa's first female ophthalmology resident & faculty member

Dr. Charlotte Burns (67R) holds a significant place in the history of the University of Iowa’s Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences. As the first female resident in the department, she broke barriers and paved the way for future generations of women in the field of ophthalmology. Her journey was marked by determination and excellence, setting a high standard for those who followed.

Dr. Burns attended both undergrad and medical school at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where her father, Bobbie Burns, was a well-known orthopedic surgeon and faculty member. After medical school she was admitted to the University of Iowa ophthalmology residency program while Dr. Alson Braley was the department head.

After finishing her residency in 1967, Dr. Fredrick Blodi, the new head of the department, invited Dr. Burns to join the faculty at Iowa. She served on faculty at Iowa from 1968 to 1971 before returning to Wisconsin to practice.

Dr. Burns' tenure at the University of Iowa was not just a personal achievement but also a milestone for the institution. Her presence in the residency program highlighted the university’s commitment to providing opportunities to underrepresented groups in medical education. She excelled in both clinical and surgical training, earning the respect and admiration of her peers and mentors. Her contributions went beyond patient care; she was also involved in research and education, helping to advance the field of ophthalmology.

One of her most notable accomplishments was her pioneering research during her time at Iowa. During her residency training she was the second author on four different publications alongside Dr. Herman Burian. Her two most cited publications came as a faculty member at Iowa. Dr. Burns' most cited publication is still "Indomethacin, Reduced Retinal Sensitivity, and Corneal Deposits," which she published, as the sole author, in 1968. She was the third author on her second most cited publication, "The Iowa enucleation implant. A 10-year evaluation of technique and results," with the first two authors as Dr. Bruce Spivey, another young faculty member at Iowa, and Lee Allen, the famous artist and ophthalmic imaging pioneer.

In addition to her research, Dr. Burns was a dedicated educator. She played a crucial role in developing the curriculum for ophthalmology residents at the University of Iowa, ensuring that the program remained at the forefront of medical education. Her commitment to teaching and mentorship helped shape the careers of many young ophthalmologists, many of whom have gone on to make their own significant contributions to the field.

Throughout her career, Dr. Burns remained a dedicated advocate for women in medicine. She mentored many young female ophthalmologists, encouraging them to pursue their dreams in the field of ophthalmology despite the challenges. Her legacy is reflected in the increasing number of women entering and excelling in ophthalmology at the University of Iowa today. Dr. Burns’ story is a testament to the impact one individual can have on an entire field, inspiring countless others to follow in her footsteps.

Facilities and Infrastructure Growth 1965-1974

To support its growing research, clinical and educational needs from 1965 to 1974, the University of Iowa's Department of Ophthalmology made significant upgrades to its facilities. Under the leadership of Dr. Frederick C. Blodi, an advanced diagnostic imaging suite was introduced, featuring state-of-the-art fundus cameras and slit-lamp biomicroscopes. Modern histology and pathology labs were established, equipped with the latest microscopes and staining techniques to support groundbreaking research in ocular diseases.

The expansion of clinical facilities included additional examination rooms, minor procedure rooms, and ambulatory surgical suites outfitted with cutting-edge surgical equipment. Specialized pediatric rooms were also created to provide tailored care for young patients, featuring child-friendly equipment and decor to ease the anxiety of young patients.

The integration of research and clinical spaces facilitated better collaboration between researchers and clinicians. This setup ensured that research findings, such as advancements in cataract surgery and glaucoma treatment, could be quickly translated into clinical practice. Regular interdisciplinary meetings and collaborative projects fostered a culture of innovation and continuous improvement within the department.

Community Outreach 1965-1974

The department's commitment to community outreach was evident through its mobile eye clinics, which traveled to rural and underserved areas in Iowa. These clinics provided essential eye care services, including screenings, treatments, and surgeries, to individuals with limited access to ophthalmic care.

Collaborations with local health organizations and community groups helped organize eye care camps and educational programs about eye health. The department also trained local healthcare providers and volunteers in basic eye care practices, ensuring continued care even after the mobile clinics had moved on.

The period from 1965 to 1974 was a time of remarkable growth and innovation for the University of Iowa's Department of Ophthalmology. Under Dr. Blodi's leadership, the department made significant strides in research, education, and community outreach. These efforts not only advanced the field of ophthalmology but also set the stage for future achievements, solidifying the department's reputation as a leader in eye care and research.